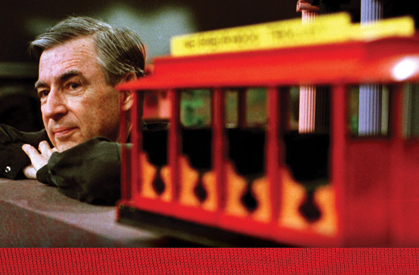

The Public Broadcast Service (PBS) program “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” had deeper meaning and more political content than the friendly Fred Rogers led you to believe. As a matter of fact, when understood in their context, including wars and social upheaval, the peaceful characters of the Neighborhood of Make-Believe reveal political messages that might surprise you.

The Public Broadcast Service (PBS) program “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” had deeper meaning and more political content than the friendly Fred Rogers led you to believe. As a matter of fact, when understood in their context, including wars and social upheaval, the peaceful characters of the Neighborhood of Make-Believe reveal political messages that might surprise you.

The PBS program celebrated the 50th anniversary of its first air date this February, a major milestone for the show that continued until its last episode on Aug. 31, 2001.

Through his love for news, a young Michael Long, who is now associate professor of religious studies and peace and conflict studies at Elizabethtown College, became interested in peace, war, conflict and the politics behind these actions. Mister Rogers came into play later, when Long saw a Public Service Announcement (PSA) featuring the television icon. Rogers’ PSA offered children a message of comfort and hope during the Persian Gulf War.

After viewing the PSA, Long started digging into who this “Mister Rogers” person was. Rogers, it turns out, was an advocate for peace as well as a quiet activist, gently sharing his beliefs on his television program. In the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, the puppet characters, on a deeper level, represented what Rogers believed the world should be like, said Long.

What these works [of the activists] do is provide me with the concrete material that gives everyday meaning to these big, abstract theories that my students read about for class.”

In his book “Peaceful Neighbor: Discovering the Countercultural Mister Rogers,” Long explored the religious, political and social beliefs that informed the television host we often associate with warm and colorful sweaters and with the importance of talking about one’s feelings to resolve conflict. His book delves into the political and religious messages that Rogers communicated through his television show.

Long has written or edited numerous books—including “Against Us, But for Us: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the State,” “The Legacy of Billy Graham: Critical Reflections on America’s Greatest Evangelist” and “First Class Citizenship: The Civil Rights Letters of Jackie Robinson.” And, with the recent anniversary of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” as well as the passing of Billy Graham, Long has been often quoted by local and national media.

The author said he uses examples from activists, such as Rogers, in his Elizabethtown College classes, where the focus is on theory, reasons why people go to war, reasons for conflict and why people perform peaceful actions. Through the work of the activists—Jackie Robinson, Martin Luther King Jr., Billy Graham and others—Long shows his students that theories discussed in class can be put into practice. “What these works [of the activists] do is provide me with the concrete material that gives everyday meaning to these big, abstract theories that my students read about for class.”

Long said he hopes “people will begin to see Fred Rogers as somebody who shared a radical political vision of what our social lives could be like if we became like those people who live in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe—and those are people who embrace peace and strive for diversity and really achieve economic justice.”