Russia, the only country that deployed female troops during World War I, nicknamed one unit the “Russian Women’s Death Battalion.” All but one of these units made it to the conflict’s front line. Their primary goal was to shame their male counterparts and boost eagerness to rejoin Russia’s war effort.

Russia, the only country that deployed female troops during World War I, nicknamed one unit the “Russian Women’s Death Battalion.” All but one of these units made it to the conflict’s front line. Their primary goal was to shame their male counterparts and boost eagerness to rejoin Russia’s war effort.

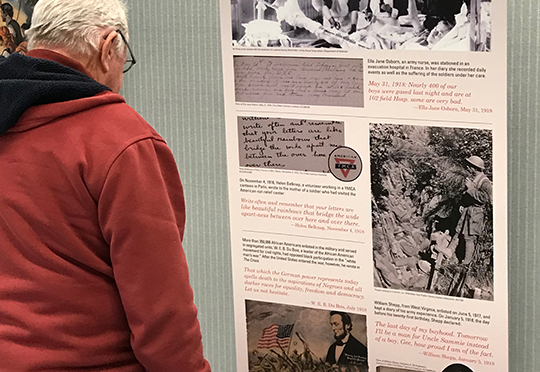

This fact was shared as part of the Feb. 14 presentation by Chelsea Schields, assistant professor of history at Elizabethtown College, to an audience of 40 students and campus community members. Schields’ lecture, “Defining the Nation: Gender, Race and Belonging During World War I,” was part of the College’s “World War I and America exhibit,” currently being showcased in the High Library.

According to Schields, women purchased war bonds, cared for soldiers on leave and took jobs in munitions factories. The munitions industry, where workers’ skin often turned yellow due to chemical exposure, saw the greatest demand for female labor, she said. “War revolutionized the industrial position of women. It found them serfs and left them free,” read Schields from a 1918 quote from British feminist, Millicent Fawcett.

People of color and women made tremendous sacrifices, and the war did not end with guarantee of their rights.”

Women were seen as being too fragile for wartime exercises, she said, sharing a quote from 1916, “women are created for the purpose of giving life, and men to take it.” Schields said that many women, however, did decide to fight. She highlighted a British woman named Flora Sandes who, in 1919, became recognized as the first woman to receive a commission into the Serbian army.

The experiences of men greatly differed from women during the war, said Schields. She referenced a historian who asserted that the conflict’s trench-warfare style created more intimate bonds between men. She spoke about another historian who observed that journals of these men reflected a desire for physical touch. Perhaps, she said, masculinity should not be purely defined by the stereotypical stoicism of men.

Schields talked about the prevalent abuse committed by Turkish troops against women. Part of the purpose of these actions, she said, was to humiliate the masculine image and suggest that men could not even protect the women in their lives.

Men returning from the war experienced “shell shock,” known today as post-traumatic stress disorder. Schields said certain soldiers developed facial tics due to close-quarter killings with bayonets to the face. Reading from a poem by Englishman Siegfried Sassoon, Schields said, “They’ll soon forget their haunted nights; their cowed Subjection to the ghosts of friends who died.”

Schields spoke about the racial barriers faced by colonial soldiers serving foreign powers. She noted that these 4 million individuals were expected to fight for freedoms they did not have. France believed its African colonial troops were “simpletons” who fought out of naïve allegiance, Schields said. In this case, she said, these troops were instructed to speak basic French, which still did not allow them to communicate effectively.

In the United States, more than one million African-Americans fought in segregated units in World War I, said Schields. One historian argued that many African-Americans hoped their military service would grant them equal rights across the entire United States, she said. Regrettably African-American veterans were treated with hostility, particularly in the South, Schields said.

In segregated units on the U.S. side were also 20,000 Puerto Ricans, said Schields. One month prior to the country’s entry into World War I, Puerto Ricans officially became U.S. citizens and soon became draft eligible with the passage of the Selective Service Act, she said.

Schields said, “People of color and women made tremendous sacrifices, and the war did not end with guarantee of their rights.”

Junior History majors Meghan Kennedy and Ben Errickson attended the lecture to support Schields and E-town’s History Club. “We want to come to all the events,” said Errickson.

Schields is currently working on the manuscript, “The Caribbean in Europe: The Politics of Intimacy after Empire,” which studies the status of gender, sexuality and reproductive issues in Europe and the Caribbean after the decline of global colonization. She teaches classes about the history of gender, sexuality and colonialism as well as Western Civilization at E-town.

Andrew Hrip Bio

Andrew Hrip is a senior at Elizabethtown College. He is majoring in English-Professional Writing and minoring in Film Studies. He writes film reviews for the College newspaper, the Etownian. He hopes to write film reviews/entertainment news for a reputable publication.