Thinking of Cuba, the initial vision probably isn’t of Chinese immigrants living and working among Cuban people. But, since the mid-1800s, Cuba has been home to a significant population of Chinese colonists who created enclaves or assimilated with the Cuban natives.

Thinking of Cuba, the initial vision probably isn’t of Chinese immigrants living and working among Cuban people. But, since the mid-1800s, Cuba has been home to a significant population of Chinese colonists who created enclaves or assimilated with the Cuban natives.

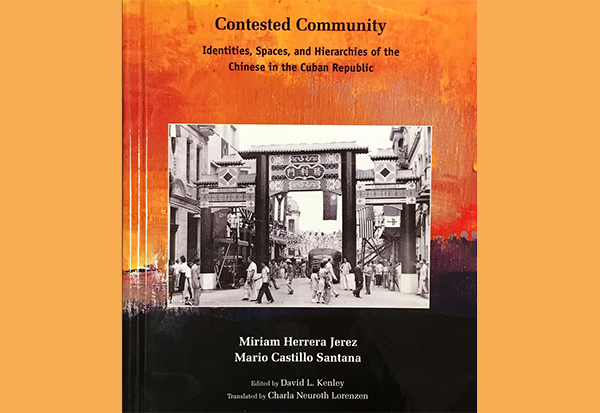

David Kenley, Elizabethtown College professor of history, was fascinated by this revelation and wanted to tell the story academically. Together with Charla Lorenzen, E-town associate professor of Spanish and Cuban colleagues Miriam Herrera Jerez and Mario Castillo Santana, he recently published “Contested Community: Identities, Spaces, and Hierarchies of the Chinese in the Cuban Republic.” The book explores how Cuba’s Chinese community was, at one time, one of the largest in the world.

“Contested Community,” edited by Kenley and translated by Lorenzen, is an analysis of the immigrant communities in Cuba between 1900 and 1968. Utilizing difficult-to-access materials from Cuba’s national archive, Kenley was able to piece together a timeline of this culture.

Chinese workers first moved to Cuba in the 1880s and 1890s as indentured sugar plantation laborers, said Kenley. “The next wave came not from China but from the U.S.” This Chinese Exclusion Act, signed in 1882, prohibited immigration of Chinese laborers. This first law that prevented specific ethnic groups from immigrating remained until 1943. In response, many Chinese Americans relocated to Cuba.

Over the years, some Cuban Chinese immigrants became wealthy, Kenley said. This created a division of classes. In the 1960s, after the Cuban Communist revolution, the wealthier Chinese left for the United States, Mexico and China. Those who stayed in Cuba, Kenley said, “assimilated; the men took Spanish wives.”

Though the professor has conducted research in numerous pockets of the world—Argentina, Costa Rica, Panama, Uruguay—until 2011 he had yet to visit Cuba. “At that time, it was difficult to get access to Cuba unless you had well-defined research.”

In 2011, along with other E-town faculty members who followed their own research paths, Kenley traveled to Cuba under a Faculty International Scholarship Seminar (FISS) grant, to explore this little-understood immigrant group.

FISS are intended for faculty members whose research will enhance teaching, professional development, research and service and is of benefit to E-town. The travel location is chosen by the College, in advance.

While in Cuba, researchers toured schools, agencies, hospitals, universities. Their access was closely monitored. “The actual research time on that trip was limited,” Kenley said.

During the trip, however, Kenley met two scholars from the University of Havana who had written a well-respected book in Spanish for a Cuban audience. Kenley wanted to translate for an English-speaking audience. He knew it would need to be heavily edited and new material would need to be added.

After gathering information to expand upon the original book, which was written in 2003 and only circulated in Cuba, it was time for interpretation.

Translation for the book was literal, said Lorenzen. “I translated directly; some were strange words for the United States.” Once translated, Kenley reviewed the translation with a fine-toothed comb, she said.

About a fifth of the book is new material added from Kenley’s research.

“David deserves 100-percent of the acknowledgment for this book. He pulled it all together. He knew about the (original) book and wanted to translate it from Spanish.”

Start to finish, Lorenzen said, the translation took 80 volunteer hours.

“I learned a ton. It was fascinating to me how welcome the Chinese were in Cuba,” she said, noting that she also found interest in the intermarriage, the Hispanic first name and Asian last name.

“There were things I didn’t know about at all before the translation.”