Glow in the dark metal. It sounds like something you’d encounter in a science-fiction movie. But an Elizabethtown College Summer Scholarship, Creative Arts and Research Projects (SCARP) venture offers the opportunity to see various metals take on luminous colors when viewed under a black light.

Jeffrey Rood and Kristi Kneas, E-town associate professors of chemistry and biochemistry, accomplished this with their students as a means of producing materials that are attractive as chemical sensors and are reliable and cost-effective in preparing for environmental and industrial applications.

SCARP gives students the opportunity to participate in independent research studies under a sponsoring faculty mentor. Through this program, students can build professional skills and gain knowledge in research areas, giving them a leg up on competition in similar career fields. Faculty members who serve as advisors and researchers benefit from students’ involvement, in support of professional scholarship and research agendas.

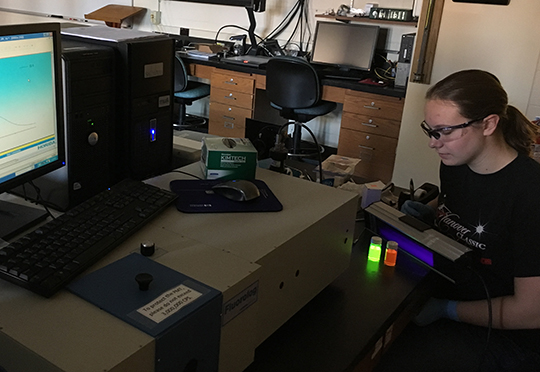

“We saw a natural fit to merge existing interests and develop a collaborative project that utilized the expertise of multiple faculty members in the department,” Rood said in an email interview. As part of this SCARP undertaking, Rood, Kneas and several students are researching the development of luminescent metal-organic frameworks as sensors. “These are porous materials that can take up small molecules into their pores,” he said. Rood and his students incorporate a luminescent molecule into the frameworks of these metals and wait for a reaction before they ultimately glow. From there, his students design materials based on the observed luminescence when certain compounds enter the pores.

“Some of the most interesting things I’ve learned while working on this project are about how the environment of the transition metal complexes can impact its luminescence,” said Kayla Hess, a junior chemistry major who has been engaged in research since her first year at E-town. Working with the metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs, said Hess, can be difficult since the environment plays such a critical role in determining luminescence.

“As a researcher, it’s my job not only to collect data but also analyze it and come up with explanations that make sense,” said Hess. Through their work, students experience the cross-disciplinary actions this type of chemical research adopts and publish their findings in international journals. “The faculty and students have the opportunity to present the work at local, regional and national meetings, and the project results are of great interest to the chemical community,” Rood said.

Rood and Kneas’ article “Water-Soluble Osmium Complexes Suitable for use in Luminescence-Based, Hydrogel-Supported Sensors” was published in September 2016 Journal of Florescence.

Rood said he believes “group dynamic” to be a driving force behind the project. Working hand-in-hand with each other and their professors, students combine their concentration within chemistry and biochemistry to fit the needs of the project. “[The students] are getting to apply many concepts that they have learned in their coursework and challenge themselves to interpret new data, make new discoveries and have a hand in progressing the project forward.”