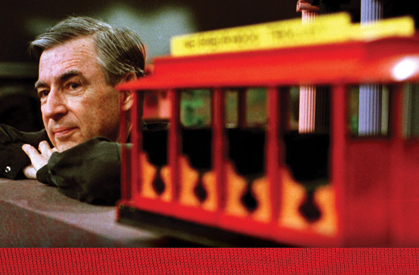

When you conjure memories of “Mister Rogers Neighborhood” flashing gently on your TV screen, remembering visits from the Queen, Trolley, Daniel Tiger and Officer Clemmons, you probably aren’t thinking about the bold political and social statements made in many of the programs. But, Fred Rogers, in his soft signature cardigan, was one of the most radical pacifists of modern history.

When you conjure memories of “Mister Rogers Neighborhood” flashing gently on your TV screen, remembering visits from the Queen, Trolley, Daniel Tiger and Officer Clemmons, you probably aren’t thinking about the bold political and social statements made in many of the programs. But, Fred Rogers, in his soft signature cardigan, was one of the most radical pacifists of modern history.

In his new book, “Peaceful Neighbor: Discovering the Countercultural Mister Rogers,” released March 13, Michael Long, associate professor of religious studies and director of Elizabethtown College’s peace and conflict studies, explores a level of Fred Rogers that most don’t consider.

“I wondered what his vision of peace looked like,” said Long, “so I went to Fred Rogers Archive in Latrobe, out near Pittsburgh, and went through his emails, his sermons, his papers…” What Long found was an undeniable correlation between significant historical events and the theme of Rogers’ shows.

“His mission, which wasn’t so obvious, was to make peace makers out of his audience.”

If you decontextualize, the show seems sappy and shallow, he said, but if you place the programs in their historical context, you can see that at volatile times Rogers did not run away but, rather, he dealt with war and peace, racial politics, economic injustice, gender equality, vegetarianism, ecological ethics and the environment.

To the children and parents who watched, the show was simple wise council for caring for one another and for treating each other with dignity; however, it seems, there were much deeper purposes for his stories. “His mission, which wasn’t so obvious, was to make peace makers out of his audience,” said Long. “If we connect the program to its historical context we can see that it’s a sharp political response to a society poised to kill. He was deeply political.”

Rogers, from Latrobe, Pa., first appeared on WQED in Pittsburgh, but on Feb. 19, 1968, Mister Rogers Neighborhood went national on public television. In the first week he ran an anti-war series; the programming continued through 2001, two years before Rogers died.

Rogers believed that the vision of peace was not just absence of war; it also means love and compassion — not just for people but for animals. In the early 1970s Rogers became a vegetarian. “He said he could never eat anything that had a mother,” Long said. When his programs showed people eating in restaurants, there was no meat in the scenes and, Long said, Rogers talked a lot about granola, tofu and beets.

“He also had a beautiful ecological ethic,” Long said of the gentle performer. He would go out on a boat and say ask the audience how they would feel if they were fish. “‘Would you want people dumping things in your home?’,” he’d ask.

His statements were powerful. Families paid attention. One of his shows featured Rogers visiting killer whale Shamu. When a rerun of the show ran soon after the release of the movie “Free Willy,” Rogers got angry letters from children asking him why he didn’t release Shamu. On another show, Rogers had a visit from Margaret Hamilton, the actress who played the Wicked Witch from Wizard of Oz. Rogers mentioned in the show that witches aren’t real, which led to reactions from the Wiccan community.

During the “white flight” of the late 1960s, in which whites began to exit racially mixed urban regions, Rogers featured a show in which he invited African Americans into his home, and he goes to their homes. “He was staking out a position with Martin Luther King,” said Long. “He was a racial integrationist.” Not long after the riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Rogers brought a black police officer character to his show, which, said Long, “showed glimpses of progressive racial politics.”

Though he wasn’t “the type to march on the streets, grab a bull horn and stand on a soap box,” Long said, “his activism occurred in the quiet of the studio and in front of a camera.”

Rogers had what Long called a Freudian instinct—to positively channel destructive emotions. “He’d say ‘it’s OK to be angry as long as we don’t hurt ourselves or one another’,” Long pointed out.

As an ordained Presbyterian minister, Rogers saw part of his mission as showing parables. “He had a sense that Jesus was a Prince of Peace,” Long said. “He wanted his followers to take up virtues of peacemaking.” Rogers, however, was asked to not talk about faith on the show.

In Latrobe, Pa., Rogers earned the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, which recognized his contribution to the well-being of children and a career in public television that demonstrates the importance of kindness, compassion and learning.

“He tried to change the hearts of people, not the just the politics of federal government,” Long said of Rogers quiet pacifism. “He tried to make children into peacemakers at an early age.”